In her thesis on Women’s Costume in French Texts of the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries, philologist Eunice Goddard often cited previous works about medieval clothing terms from various 19th century costumers. Although more recent scholarship has often come to different conclusions than these earlier writers, understanding what they said is helpful in a drawing out a fuller picture of the topic. This is especially important as Goddard continues to be held as a go-to source for re-enactors.

At the beginning of her entry on the “Ceinture“, or dress belt, she referred her readers to four such works, writing:

“The ceinture is a belt worn with the dress. The elaborate and costly belts worn at this period have been described at length in the histories of costume. cf. Viollet-le-Duc, III, 104 ; Enlart, 273 ; Schultz, I, 204 ; Weinhold, II, 281.”

I intended to place each of these references in a separate blog post. This is the first of the four.

Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire du mobilier français

Vol. 3, pg. 104ff

L’influence des vêtements byzantins fut telle sur les modes françaises , pendant la première moitié du xIIe siècle, que les ceintures ne firent plus partie du vêtement civil des hommes nobles (voy. ROBE). Elles furent au contraire de mise pour les vêtements desfemmes et d’une extrême richesse.

During the first half of the twelfth century, Byzantine clothing had such influence on the French styles that that the belts were no longer part of the everyday clothing of noble men (see ROBE). In contrast, they were emphasized in women’s clothing, and with great richness.

Cette ceinture (fig. 3), posée sur le ventre, à la hauteur des hanches, était croisée par derrière, retombait à la jonction du corsage du bliaut * avec la jupe. Là elle était nouée lâche et laissait pendre deux longs bouts de soie tressée “. Couverte d’une passementerie ornée d’orfévrerie, la ceinture devenait souple au point où le nœud devait être fait; c’est ce qu’explique la figure 4. Ces bouts A étaient composés de ganses de soie tressées ou juxtaposées, serrées de distance en distance par des bagues d’orfévrerie B. Quand on observe comme était fait le bliaut, comme la jupe de ce vêtement était retenue au corsage, cette ceinture devenait nécessaire pour dissimuler la jonction de ces deux parties de l’habit. Quelquefois elle ne consistait qu’en une longue bande d’étoffe très-riche, comme une sorte d’écharpe étroite.

Cette ceinture (fig. 3), posée sur le ventre, à la hauteur des hanches, était croisée par derrière, retombait à la jonction du corsage du bliaut * avec la jupe. Là elle était nouée lâche et laissait pendre deux longs bouts de soie tressée “. Couverte d’une passementerie ornée d’orfévrerie, la ceinture devenait souple au point où le nœud devait être fait; c’est ce qu’explique la figure 4. Ces bouts A étaient composés de ganses de soie tressées ou juxtaposées, serrées de distance en distance par des bagues d’orfévrerie B. Quand on observe comme était fait le bliaut, comme la jupe de ce vêtement était retenue au corsage, cette ceinture devenait nécessaire pour dissimuler la jonction de ces deux parties de l’habit. Quelquefois elle ne consistait qu’en une longue bande d’étoffe très-riche, comme une sorte d’écharpe étroite.

This belt (Fig. 3), was placed across the stomach at the height of the hips, crossed in behind, and fell where the bodice and the skirt of the bliaut joined. There it was tightly knotted and allowed to hang two long ends of braided silk. Covered in decorative gold-work trim, the belt became flexible at the point where the knot needed to be made, which is explained in Figure 4. These ends were made of lengths of silk, braided or interwoven, and held tight at intervals by golden rings. (B). When one observes how the bliaut was made, how the skirt of this garment was attached to the bodice, this belt became necessary in order to hide the seam between these two parts of the gown. Sometimes it consisted only of a long band of very rich fabric, like a sort of narrow scarf.

This belt (Fig. 3), was placed across the stomach at the height of the hips, crossed in behind, and fell where the bodice and the skirt of the bliaut joined. There it was tightly knotted and allowed to hang two long ends of braided silk. Covered in decorative gold-work trim, the belt became flexible at the point where the knot needed to be made, which is explained in Figure 4. These ends were made of lengths of silk, braided or interwoven, and held tight at intervals by golden rings. (B). When one observes how the bliaut was made, how the skirt of this garment was attached to the bodice, this belt became necessary in order to hide the seam between these two parts of the gown. Sometimes it consisted only of a long band of very rich fabric, like a sort of narrow scarf.

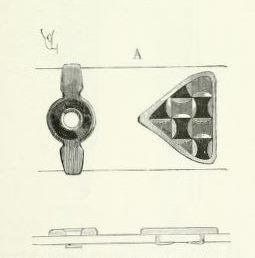

A la fin du xII° siècle, le vêtement civil des hommes se modifia complétement : plus de robes longues à manches démesurément larges ; plus de ces passementeries entremêlées de pierreries. La tunique ne descend que jusqu’aux chevilles, elle est à manches étroites ; le bliaut la recouvre parfois, et une ceinture étroite ceint habituellement la taille. Il en est de même pour les femmes, si ce n’est que la robe descend sur les pieds 1. La figure 5 présente une de ces ceintures d’hommes nobles, pendant la première moitié du xIII° siècle. Sur la courroie sont rivées des plaques de métal doré ou émaillé 2, dont nous donnons un détail, grandeur d’exécution, en A, et qui étaient destinées à empêcher cette courroie, faite de cuir souple ou même d’un tissu de soie, de se plisser.

A la fin du xII° siècle, le vêtement civil des hommes se modifia complétement : plus de robes longues à manches démesurément larges ; plus de ces passementeries entremêlées de pierreries. La tunique ne descend que jusqu’aux chevilles, elle est à manches étroites ; le bliaut la recouvre parfois, et une ceinture étroite ceint habituellement la taille. Il en est de même pour les femmes, si ce n’est que la robe descend sur les pieds 1. La figure 5 présente une de ces ceintures d’hommes nobles, pendant la première moitié du xIII° siècle. Sur la courroie sont rivées des plaques de métal doré ou émaillé 2, dont nous donnons un détail, grandeur d’exécution, en A, et qui étaient destinées à empêcher cette courroie, faite de cuir souple ou même d’un tissu de soie, de se plisser.

At the end of the twelfth century, men’s civilian clothing changed completely: no more long robes with disproportionately large sleeves; no more trim decorated with jewels. The tunic descended only to the ankles, and with straight, narrow sleeves. Sometimes a bliaut would cover it, and a narrow belt typically belted the waist. It was the same for women, except that the dress descended to the feet. Figure 5 presents one of these belts of noble men, from the first half of the thirteenth century. Along the length are riveted plaques of gilded or enamelled metal, which are shown in more detail in A, and which were intended to prevent this belt, made of soft leather or even silk fabric, from folding and bending.

At the end of the twelfth century, men’s civilian clothing changed completely: no more long robes with disproportionately large sleeves; no more trim decorated with jewels. The tunic descended only to the ankles, and with straight, narrow sleeves. Sometimes a bliaut would cover it, and a narrow belt typically belted the waist. It was the same for women, except that the dress descended to the feet. Figure 5 presents one of these belts of noble men, from the first half of the thirteenth century. Along the length are riveted plaques of gilded or enamelled metal, which are shown in more detail in A, and which were intended to prevent this belt, made of soft leather or even silk fabric, from folding and bending.

One thought on “Viollet-le-Duc on the Ceinture (Dress Belt)”